Ritual and

ceremonial buildings

Zuo Zhuan (The Commentary of Zuo) stated, “The major affairs of a nation lie in its rituals and military.” Offering sacrifices was part and parcel of the ritual tradition of ancient China, boasting a system rich in content and complex in logic. The worshiping objects, ritual activities, and event procedures were clearly defined.

Located on both sides of Beijing Central Axis, the four groups of altars and temple buildings, namely the Imperial Ancestral Temple, the Altar of Land and Grain, the Temple of Heaven, and the Altar of the God of Agriculture, are the best-preserved imperial sacrificial buildings in China in terms of planning, architectural form, decorative art, and construction techniques. They form a powerful material witness to the national sacrificial system in China during the Ming and Qing dynasties.

The ritual system embodied by the four altars and temples are dedicated to three main categories of gods: the gods of heaven, the deities of ancestors, and the gods of the earth. The gods of heaven are headed by Hao Tian (an abstract concept of the will of heaven or nature) and include celestial bodies and natural phenomena such as the sun, the moon, stars, clouds, rain, wind, and thunder. Ancestors mainly refer to the deceased emperors of the dynasty. The earth gods are headed by Tai She (the God of Land) and Tai Ji (the God of Grain), including mountains, rivers, forests, and marshlands.

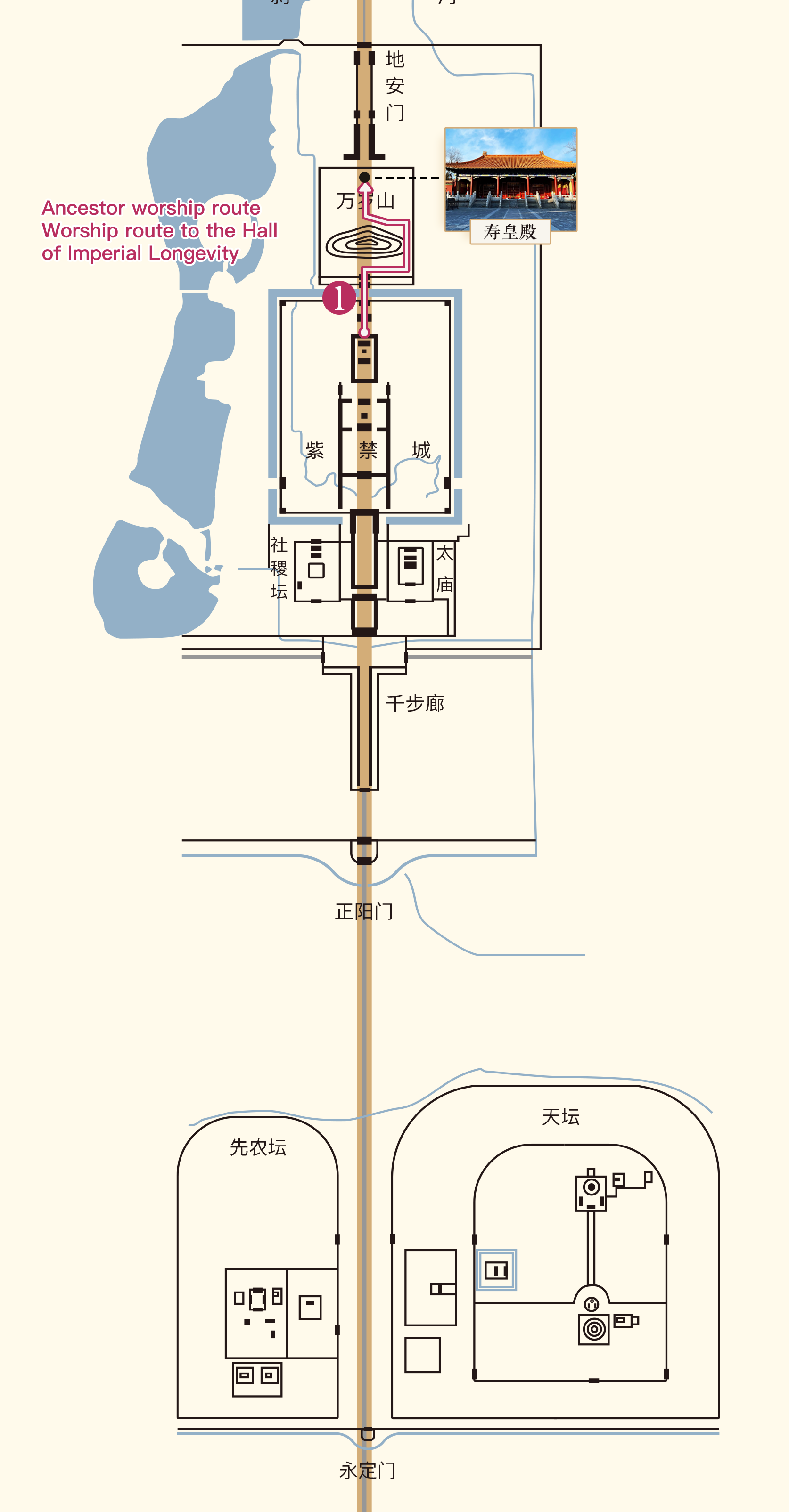

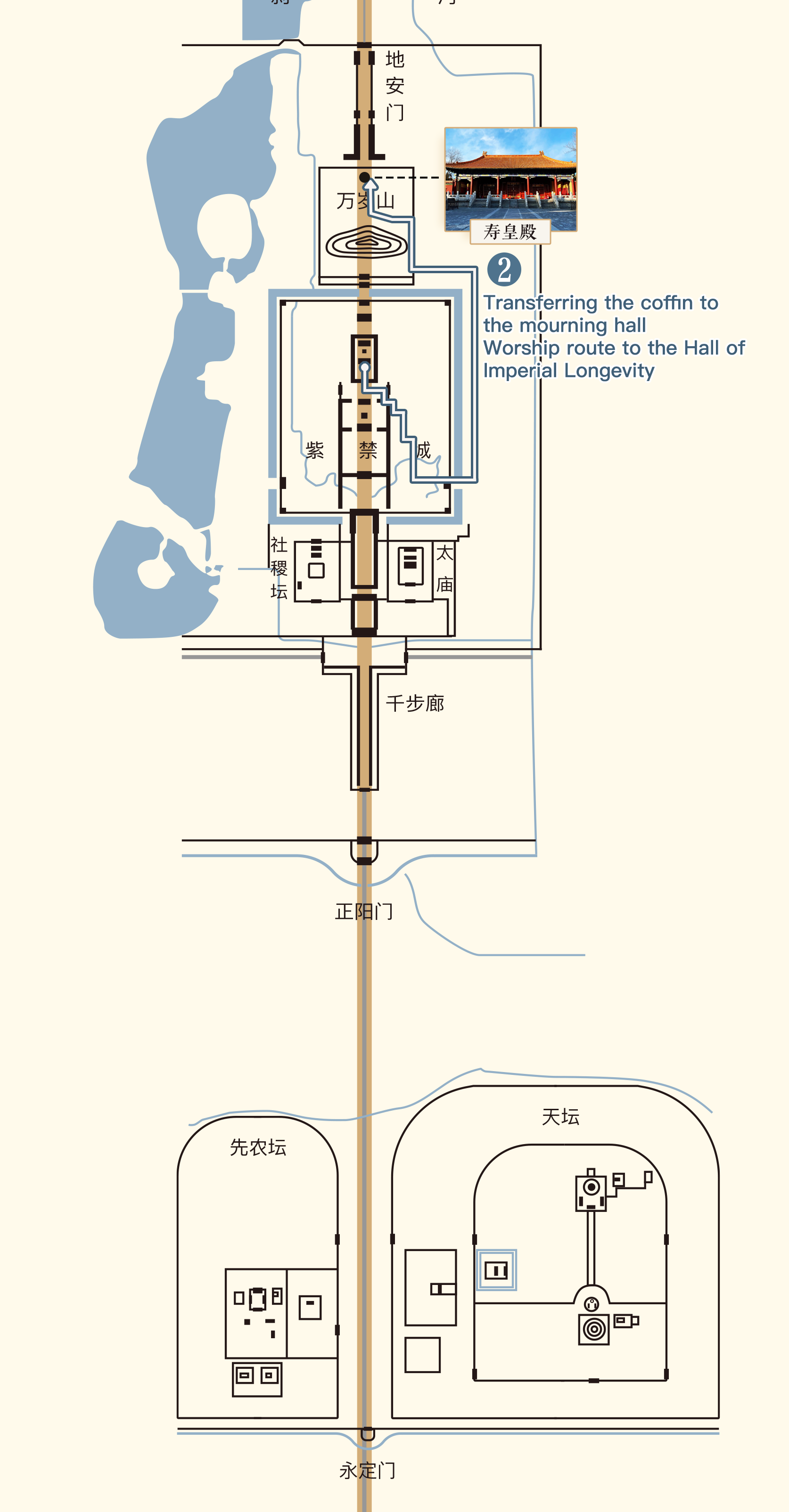

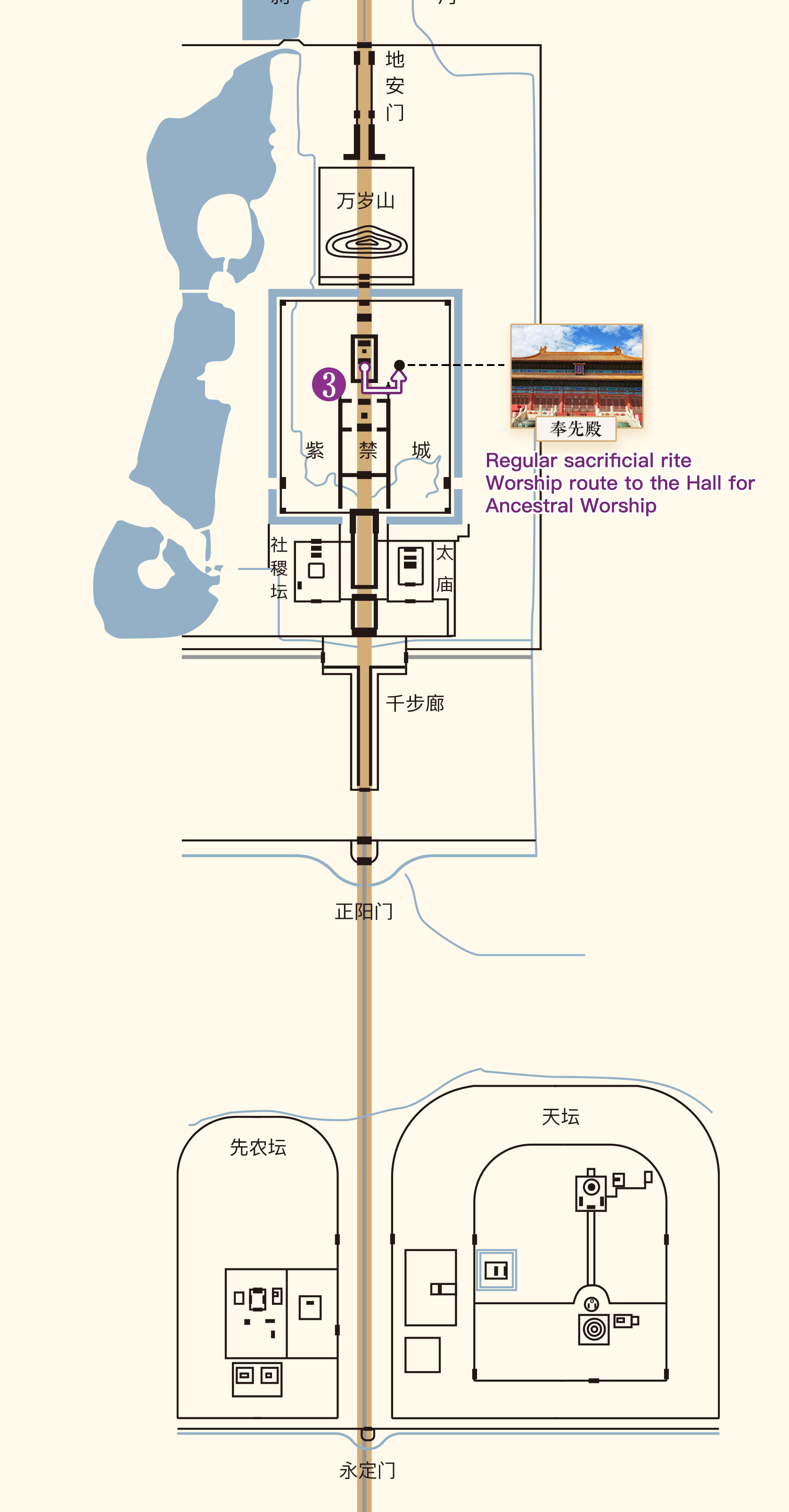

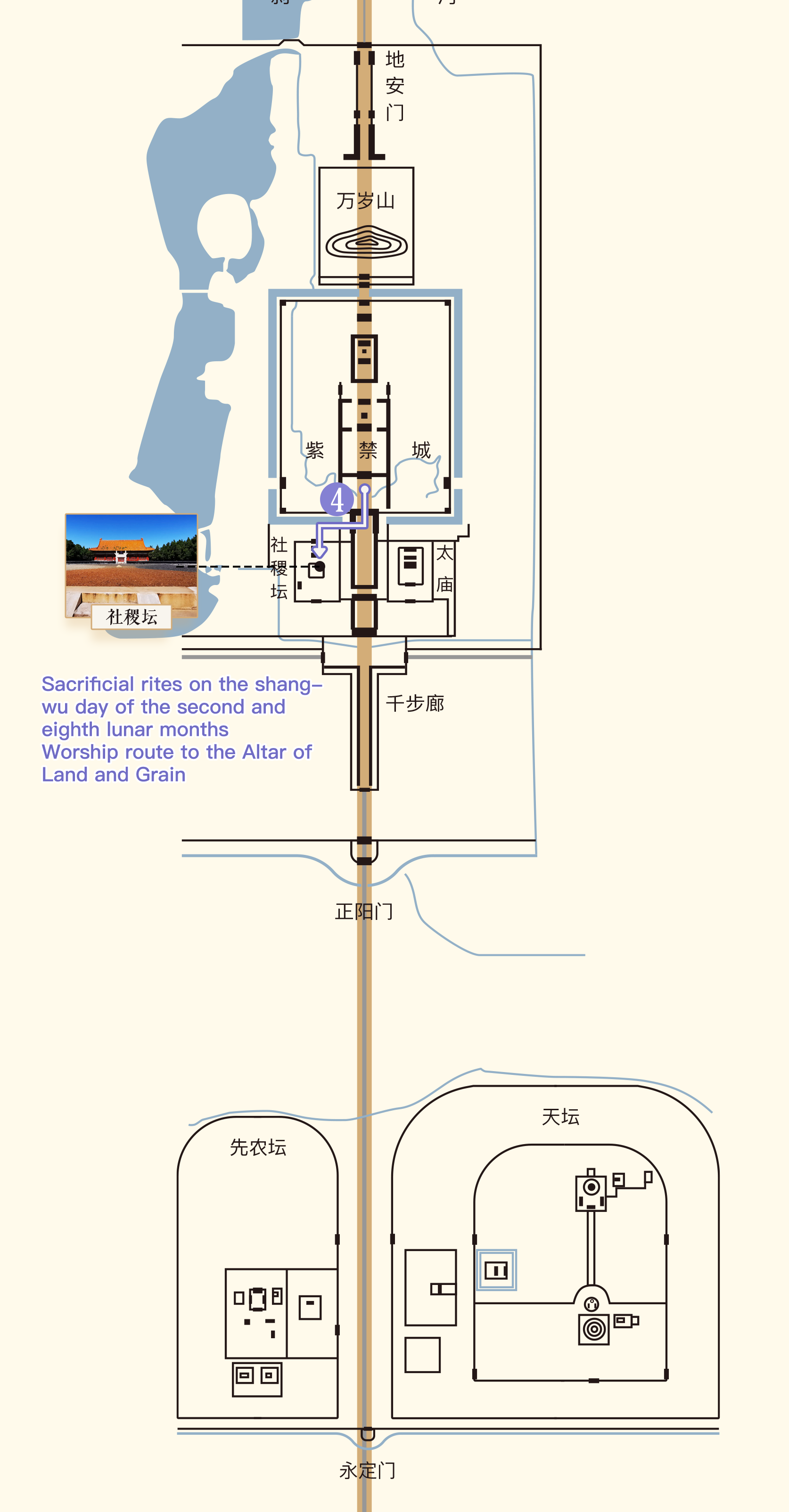

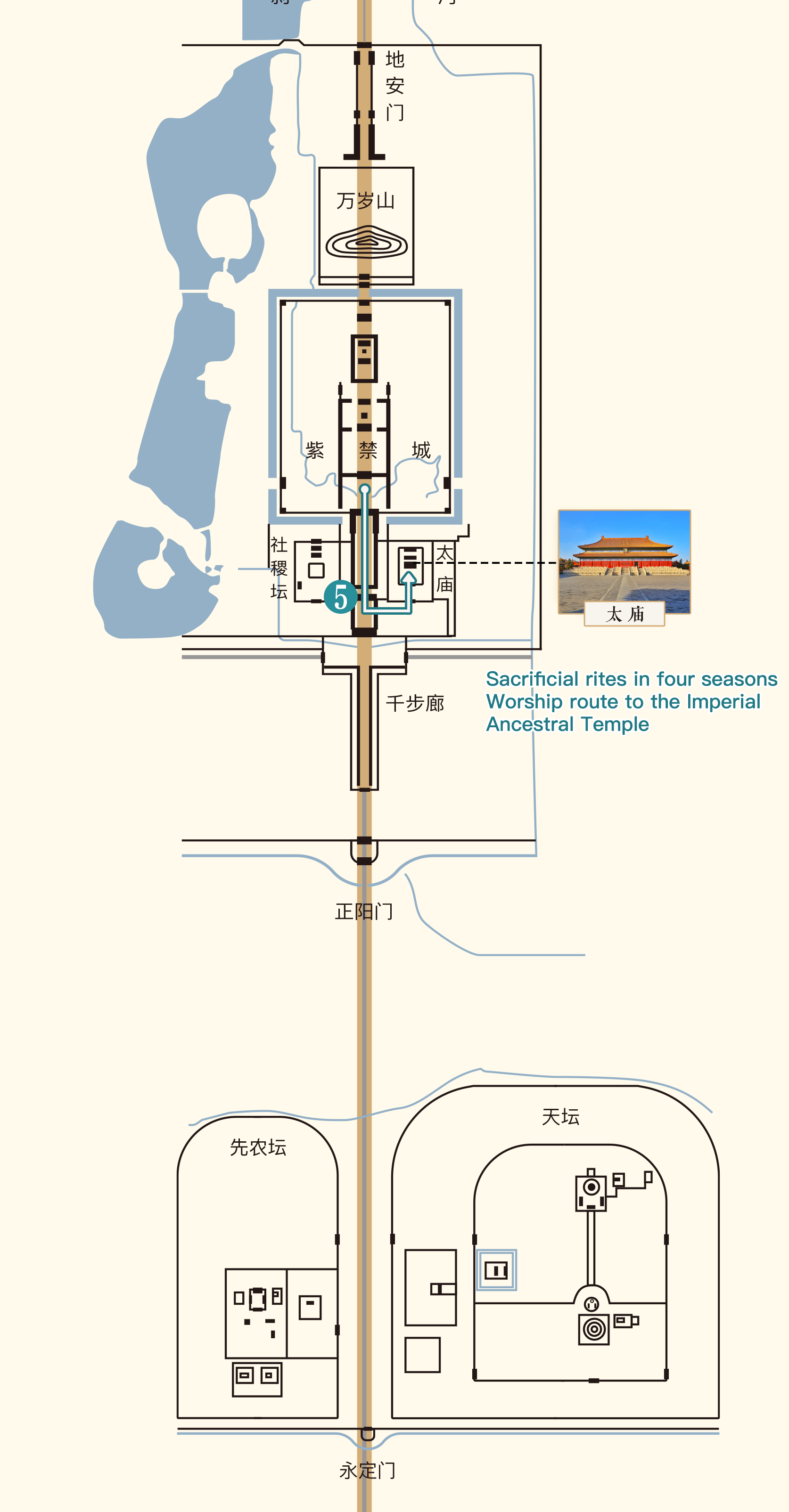

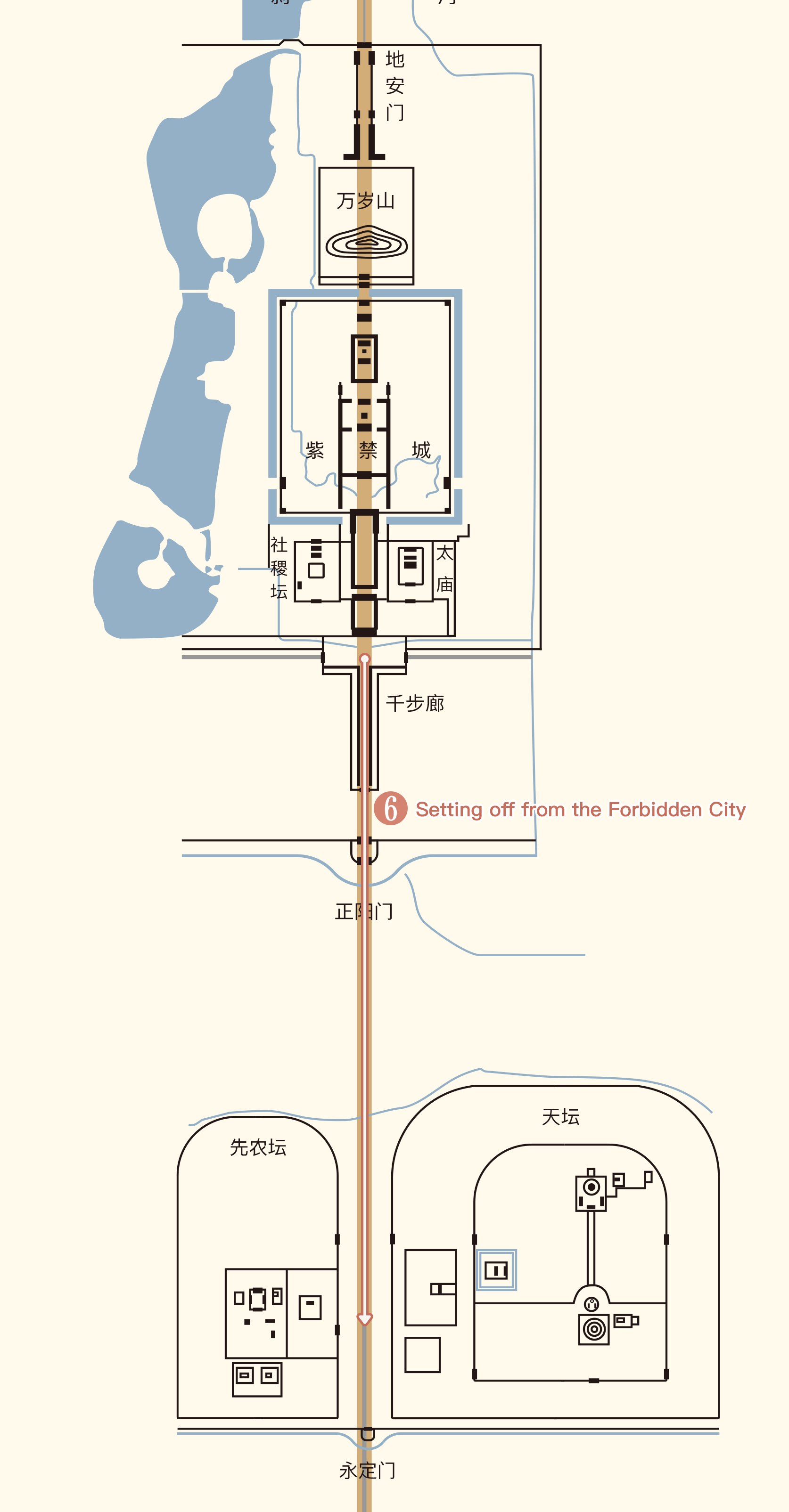

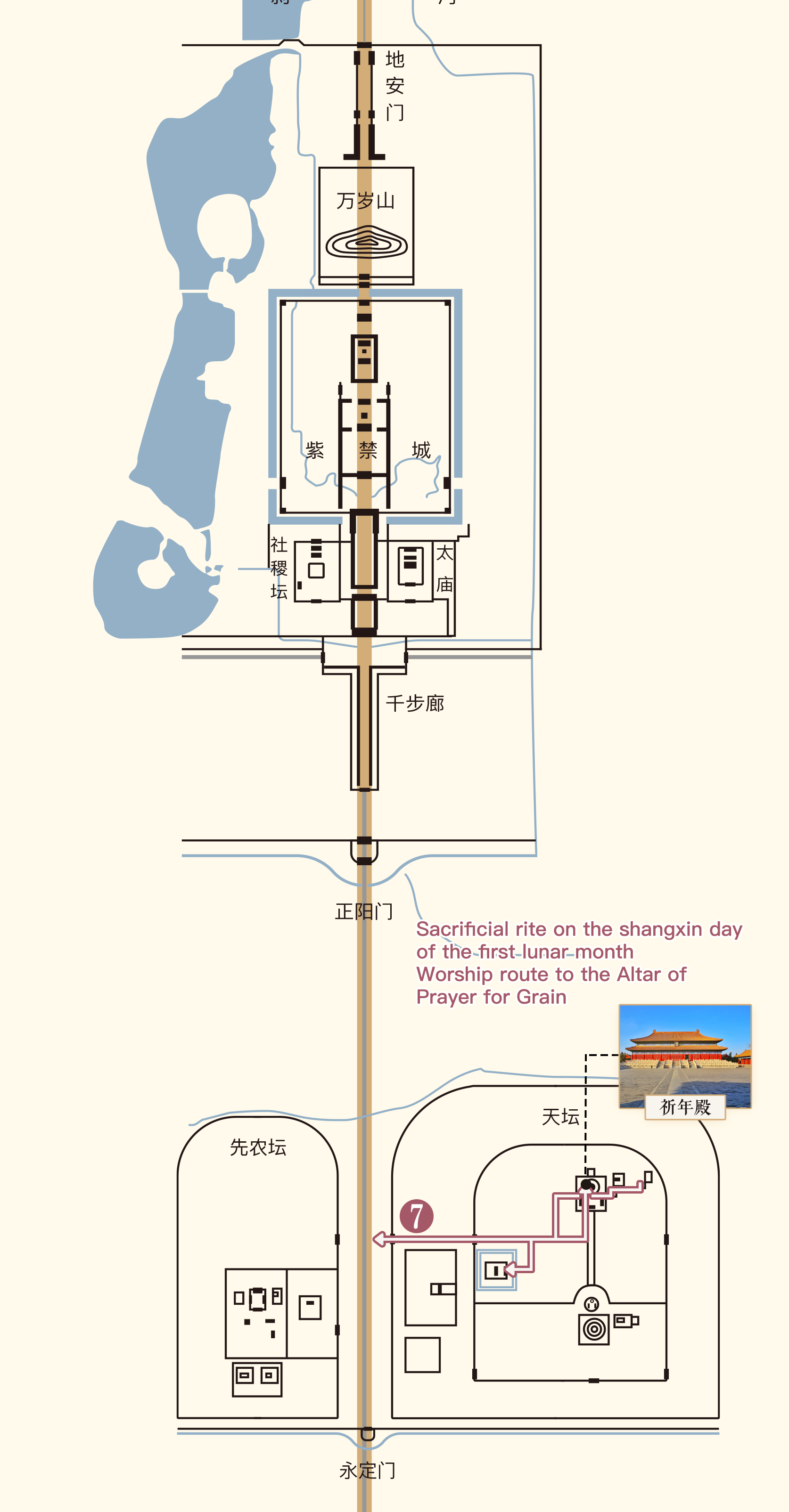

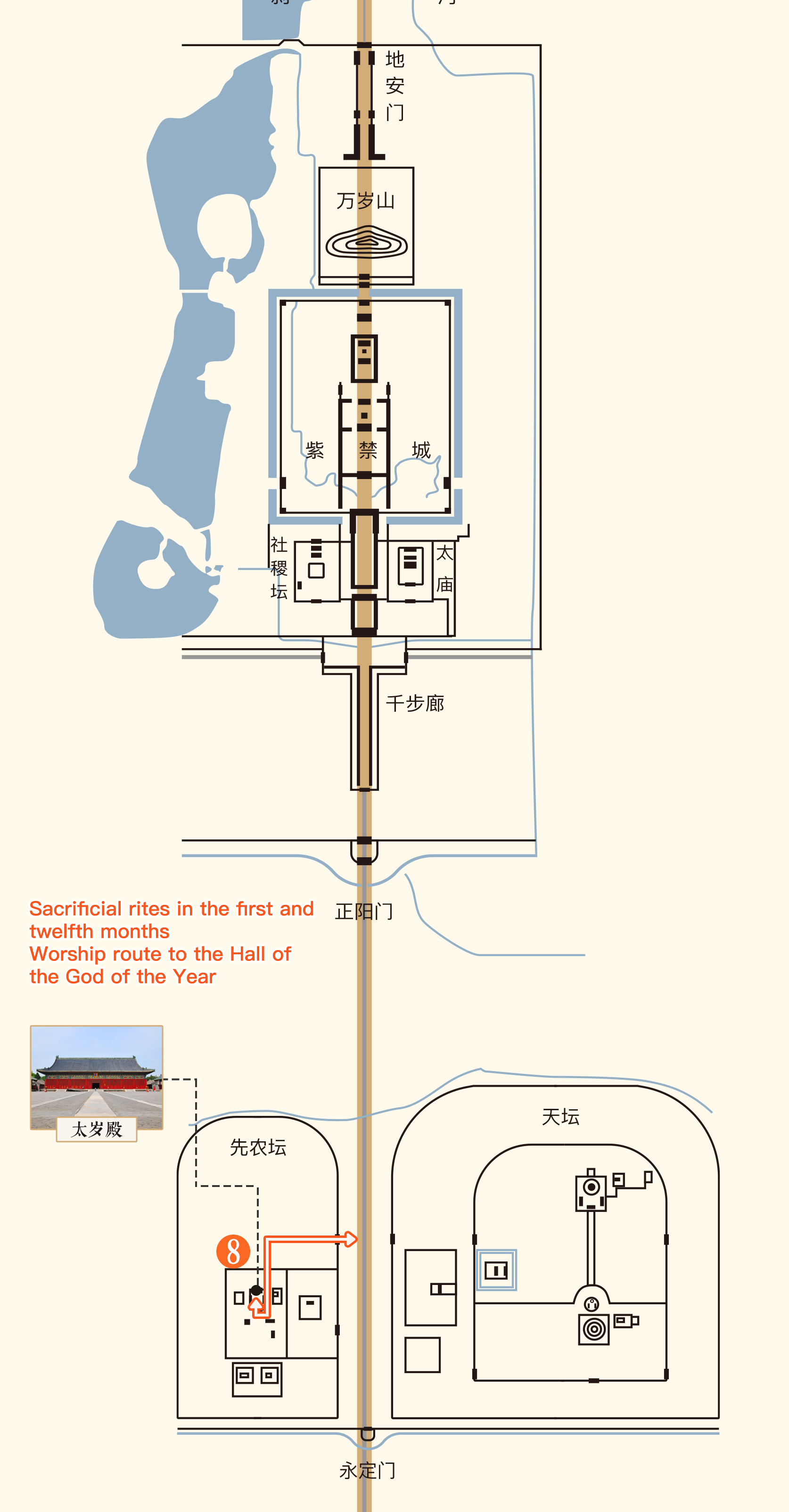

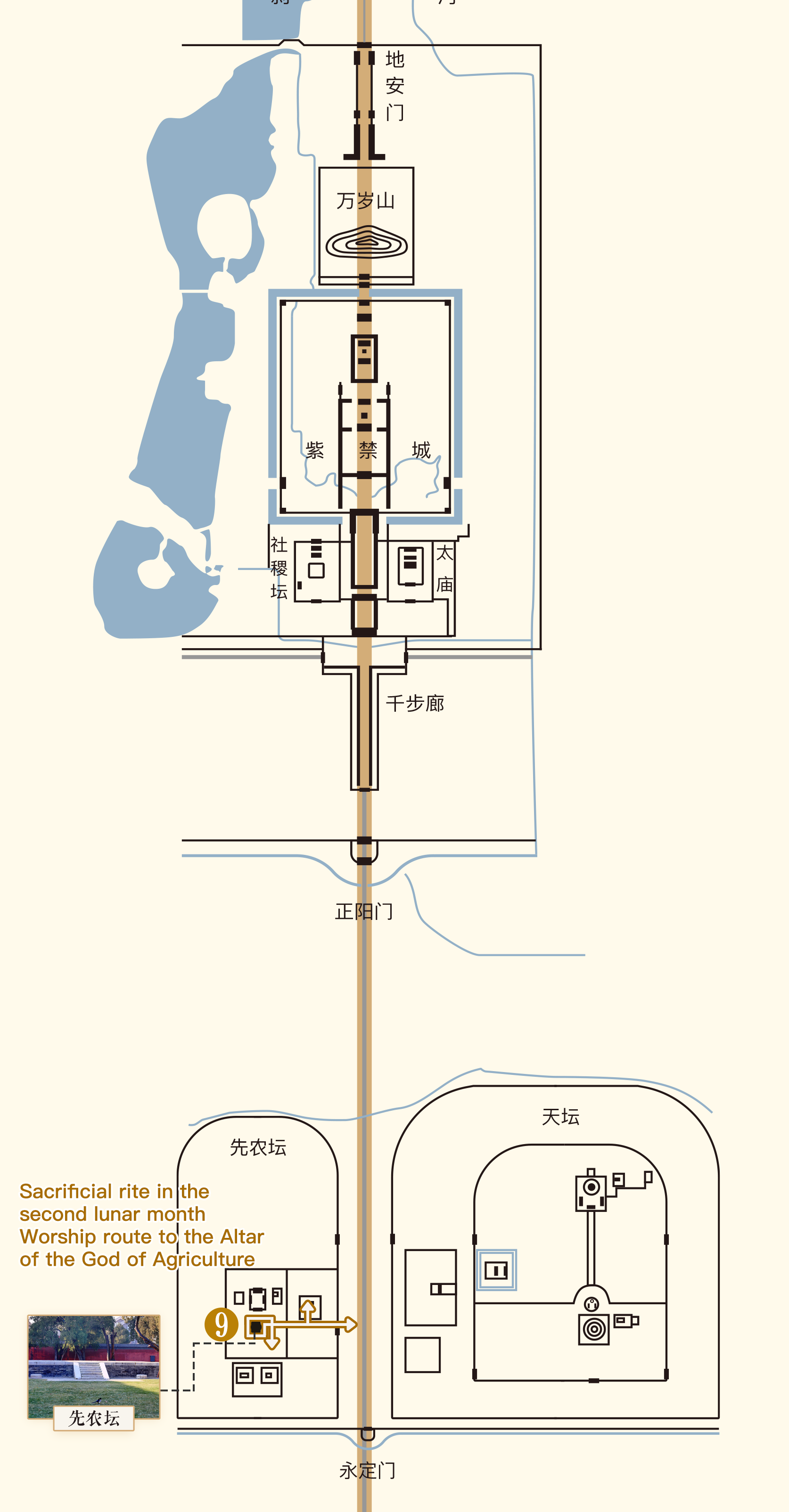

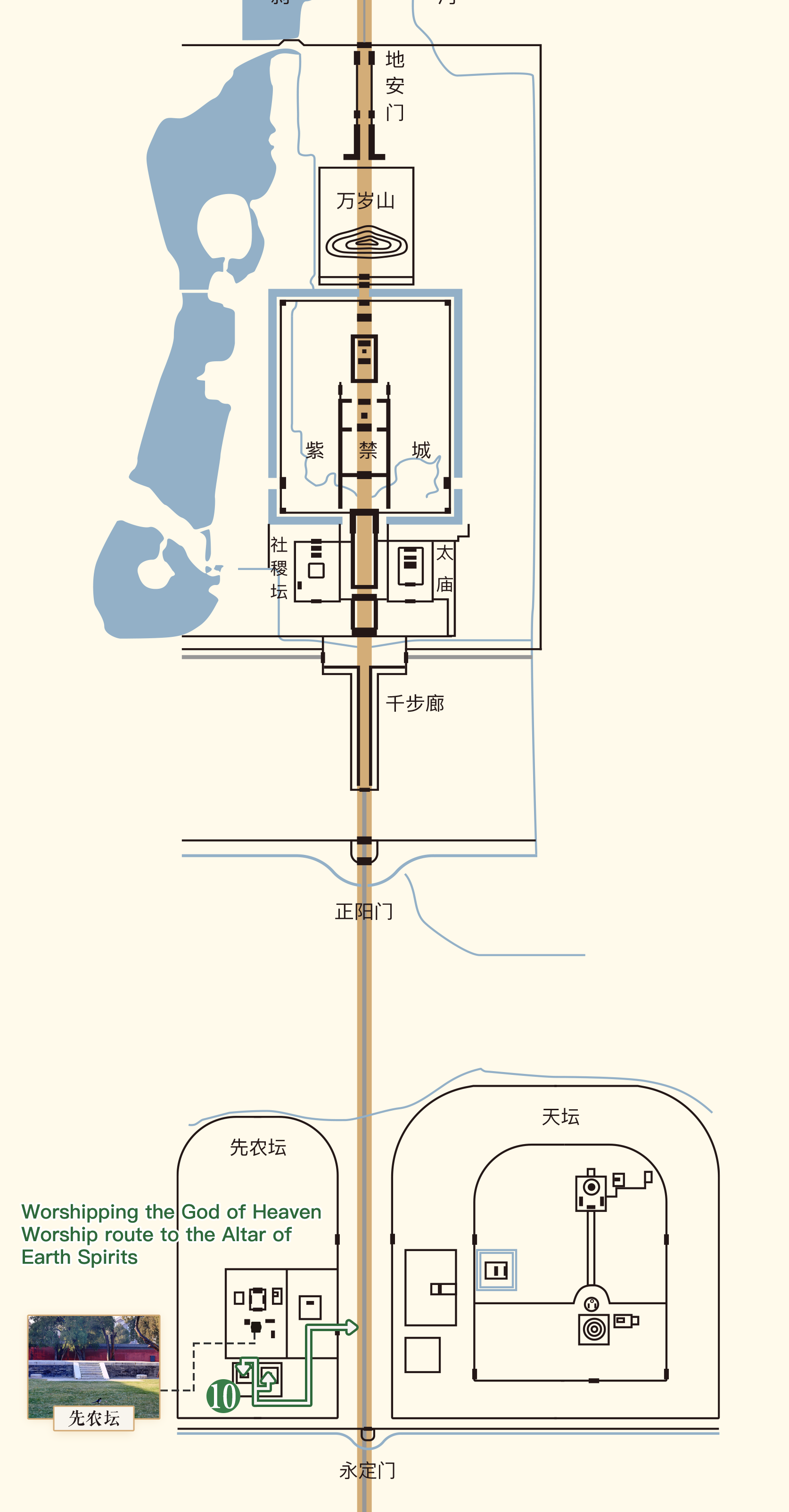

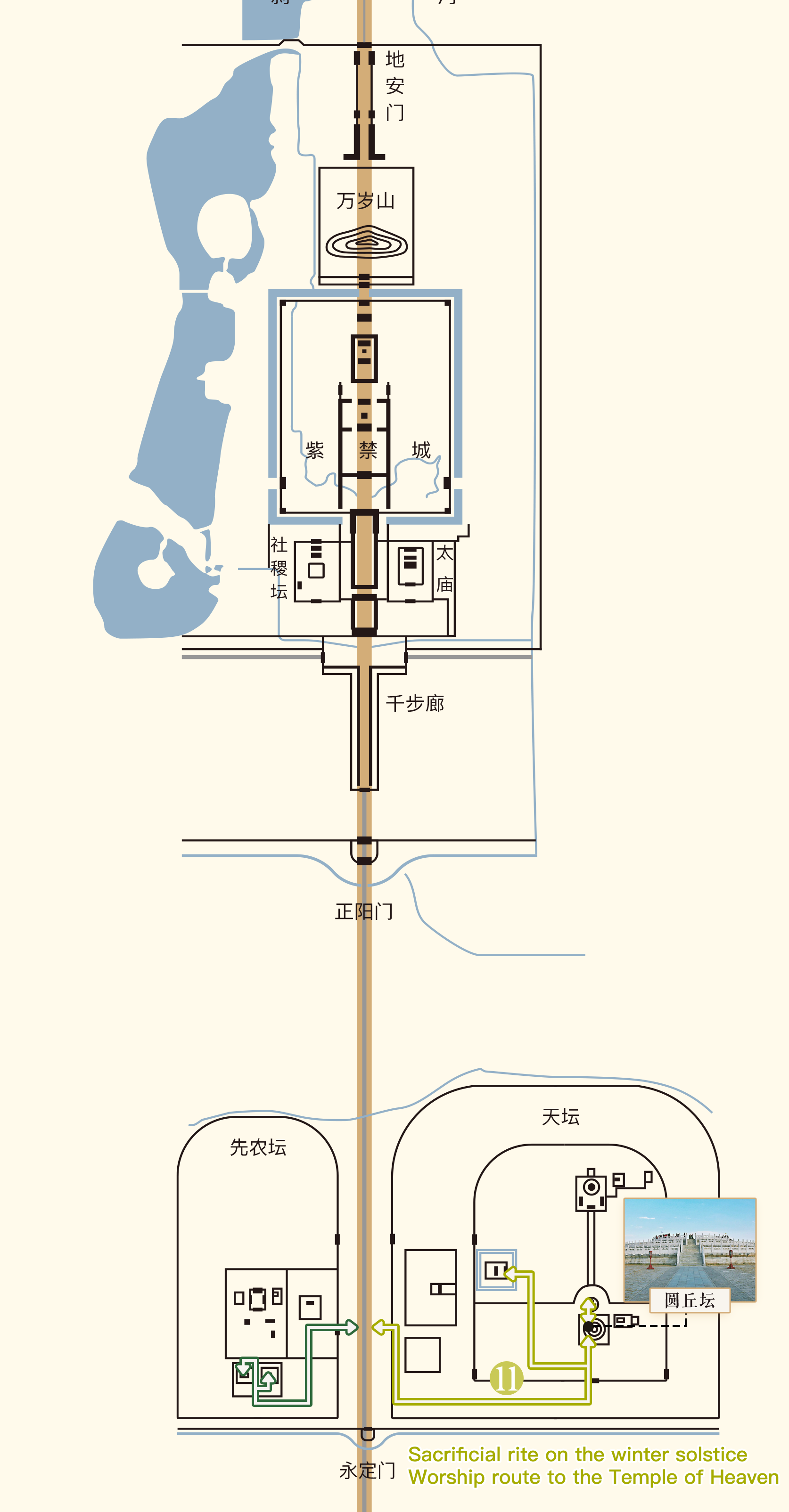

![]() Redrawn illustration: The route map of the sacrificial rituals on Beijing Central Axis

Redrawn illustration: The route map of the sacrificial rituals on Beijing Central Axis

Source: Drawn by the THAD team for preparing the nomination dossier of Beijing Central Axis and transferred by Tencent

Reference: Qing Huidian (Codes of Qing) [M], Zhonghua Book Company, 2013

Serving the imperial families of the Ming and Qing dynasties, the Imperial Ancestral Temple is the material carrier of the Chinese cultural tradition of “worshiping the ancestors.” It is an essential building for national rituals and the most complete and largest extant building complex of ancestral worship by the imperial families. Making sacrifices to the ancestors has a strong ethical significance in traditional Chinese culture, expressing the moral code - respected in ancient society - of “filial piety as the basis of virtue.”

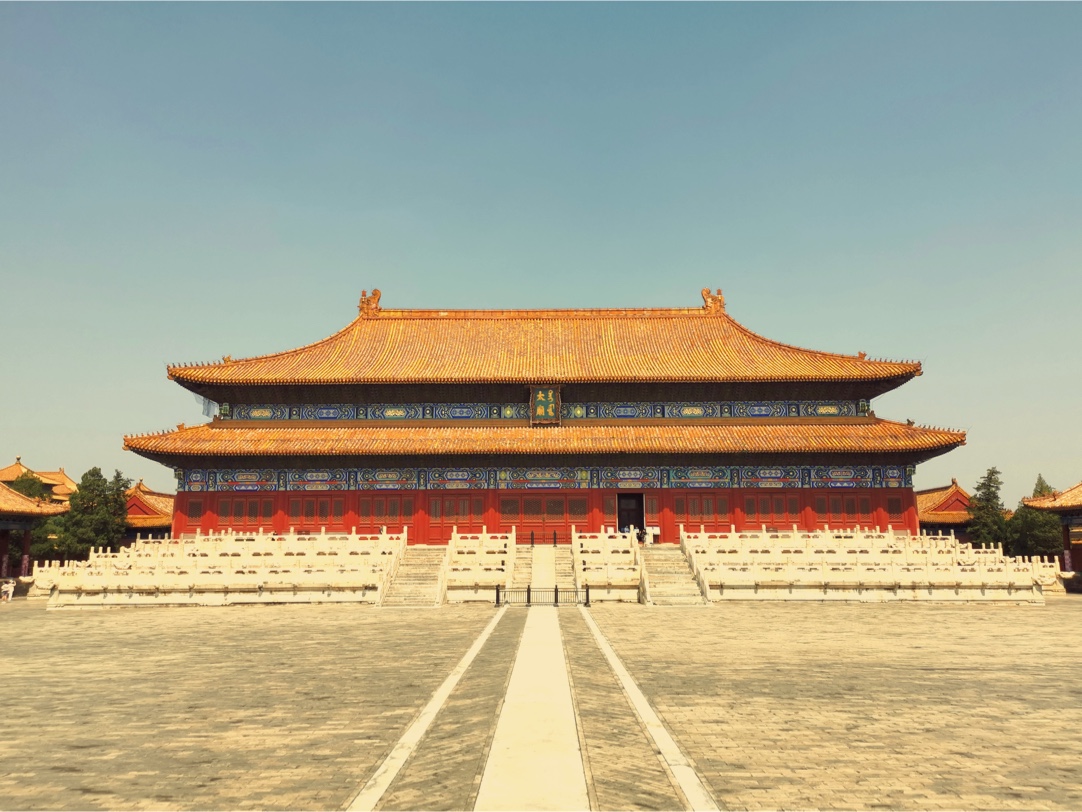

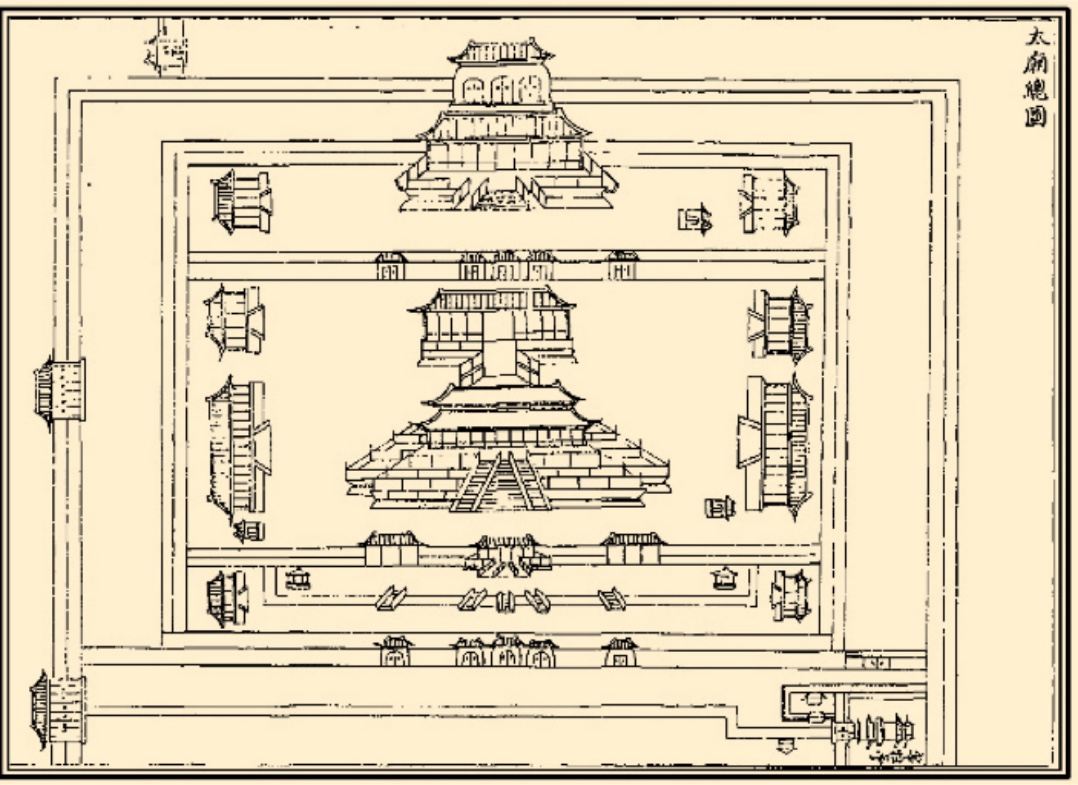

The pair of adjacent sacrificial buildings comprising the Imperial Ancestral Temple and the Altar of Land and Grain are symmetrically aligned along the axis. This section of Beijing Central Axis boasts the highest-grade of ancient architecture, which constitutes the most splendid part of the cityscape. The rigorously symmetrical layout of the Imperial Ancestral Temple and the Altar of Land and Grain on Beijing Central Axis embodies the ideal capital city’s planning paradigm as prescribed in the Kaogongji. The Sacrificial Hall, the Resting Hall, and the Distant Kin Temple are on a central axis running from south to north. The Sacrificial Hall of the Imperial Ancestral Temple was designed as a palatial-style structure, and to emphasize the importance of ancestor worship, it was constructed in the highest form of the office building in the Ming and Qing dynasties. The imperial ancestors’ spirit tablets were placed in the Resting Hall on normal days. The Distant Kin Temple was where the spirit tablets of the distant imperial ancestors were enshrined.

Unlike the Hall for Ancestral Worship inside the Forbidden City, where the emperors could worship their ancestors at any time, worshiping at the Imperial Ancestral Temple must happen at specific times, which means that it would not open until the royal ceremony of offering sacrifices occurred. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, the sacrificial ceremonies performed in the Imperial Ancestral Temple comprised four different types of worship: the shixiang (seasonal); xiaji (new year); jianxin (sacrificing fresh food); and gaoji (informing ancestors of what happened in this world). Shixiang refers to the sacrificial rites in honor of the imperial ancestors at the beginning of each season. Xiaji was a ritual by which all the spirit tablets in the Resting Hall and the Distant Kin Temple were temporarily moved to the Sacrificial Hall for a sacrificial ceremony. Starting from 1659, the xiaji was held at the end of each year. Gaoji refers to unconventional sacrifices, and the time of the rituals was irregular. It was performed to seek ancestors’ advice in the event of major incidents affecting the country.

Imperially Endorsed Collection of Statutes of the Great Qing

Imperial Ancestral Temple in the painting of the Qing dynasty.

The Altar of Land and Grain is the most complete extant ancient imperial altar in China that was used to worship Tai She (the God of Land) and Tai Ji (the God of Grain). Land and grain constituted the basis for building up and stabilizing China as a country emphasizing agriculture. Offering sacrifices to Tai She and Tai Ji was not only significant to land and grain, but it also emphasized the importance of the country’s territories. Therefore, praying for consolidating the country’s foundation, prosperity, and territorial integrity was of great significance. Worshiping Tai She and Tai Ji emphasized the impact of land and grains on China and its society, thereby closely linking the country and social order with the relationship between man and earth.

Located west of the Imperial Ancestral Temple, the Altar of Land and Grain has two altars: the inner and the outer, with the sacrificial altar platform in the inner altar. The Altar of Land and Grain is square-shaped. The altar top is spread with “five-colored earth” collected from across the country to embody the idea that “all the land under heaven belongs to the emperor.” The five colors, namely blue, red, white, black, and yellow, represent the five elements of nature and all cardinal directions: east, south, west, north, and center. They symbolize the concept of “all the land under heaven belonging to the sovereign.”

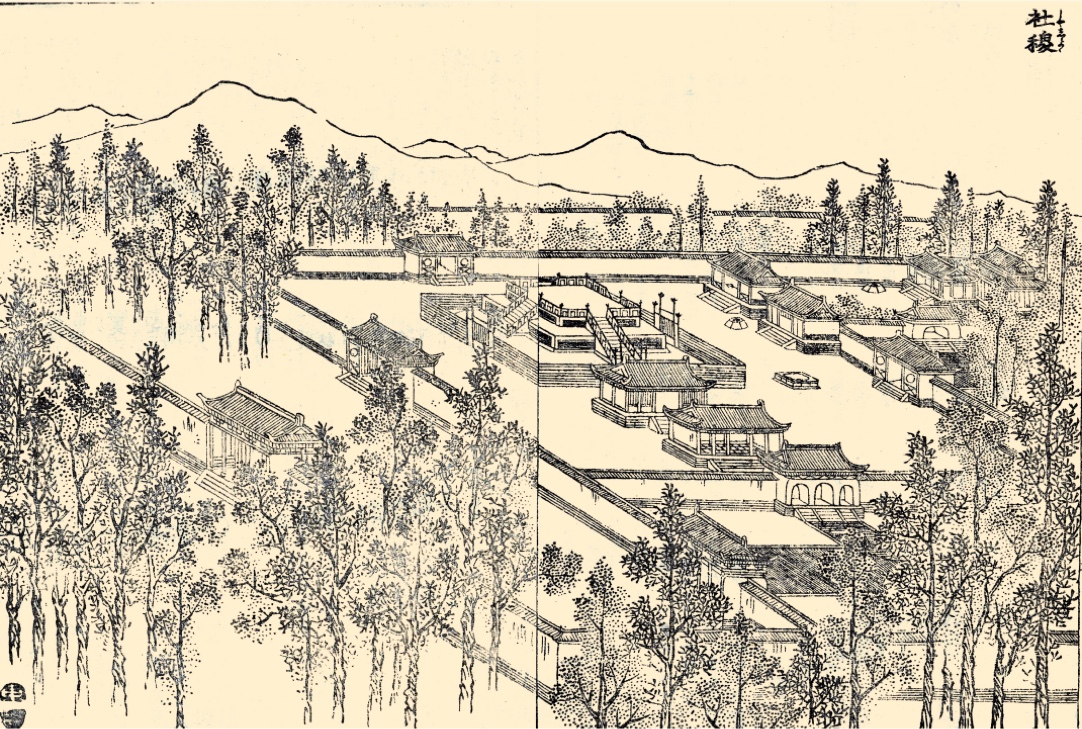

Collected Illustrations of Famous Scenery in the Land of the Tang.

The Altar of Land and Grain of the Late Qing Dynasty displayed

The changsi sacrificial ceremony was performed in early mid-spring and mid-autumn. Gaoji refers to unconventional sacrifices, and the time of the rituals was irregular. It was performed to seek ancestors’ advice in the event of major incidents affecting the country. The route for the rituals ran from north to south, different from the orientation during the sacrificial rites at the Imperial Ancestral Temple and the Temple of Heaven. This difference reflects the traditional Chinese concept that the gods of the land are yin (negative, contrasting with the gods of heaven or deities of ancestors, which are yang and positive).

The current status of the Altar of Land and Grain

The altar top is spread with “five-colored earth” collected from across the country. The five colors, namely blue, red, white, black, and yellow, represent the five elements of nature and all cardinal directions: east, south, west, north, and center.

The Temple of Heaven was the venue to offer sacrifices to the Supreme Deity of Heaven. The ritual of offering sacrifices to the heavens is an important embodiment of the ancient Chinese concept of “the divine bestowal of imperial power,” indicating that emperors received their mandate from heaven and possessed a lofty status.

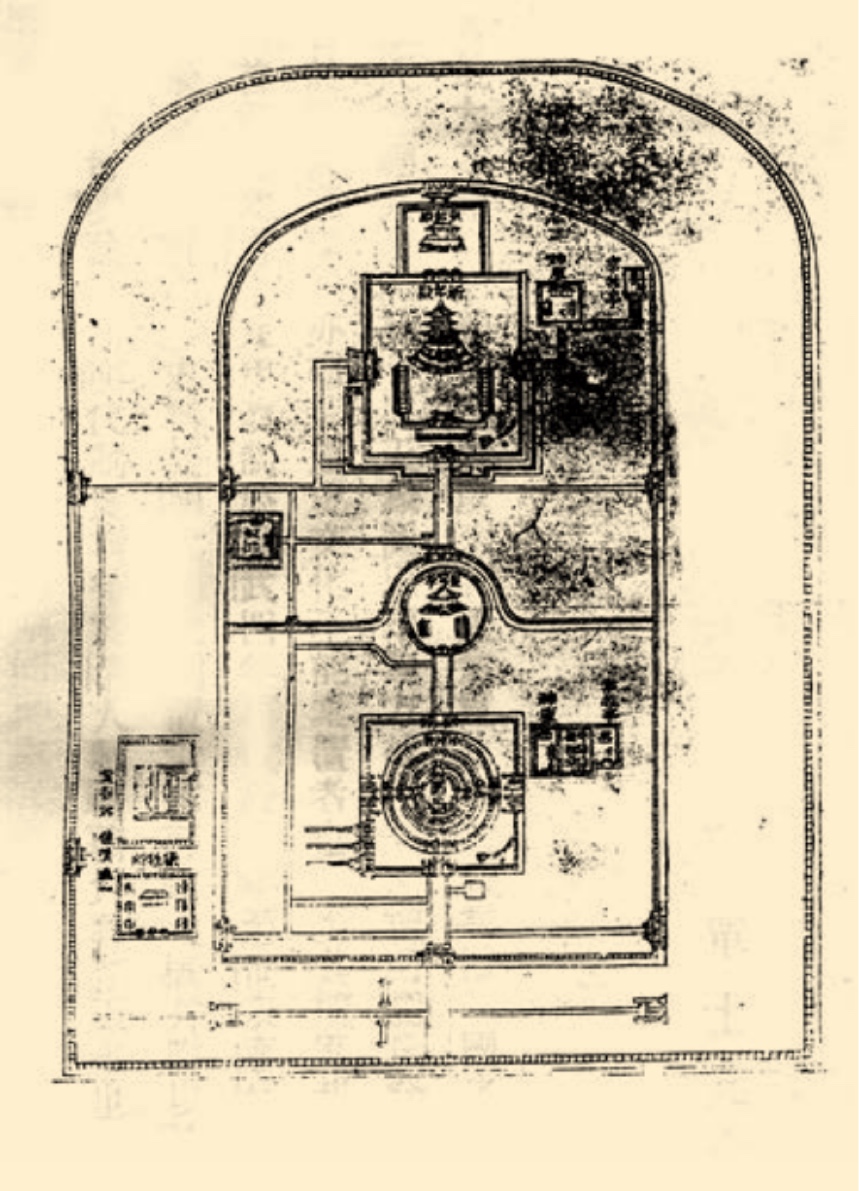

The inner and outer altar walls are round in the north and square in the south, representing the ancient belief that “heaven is round and earth is square.” The Altar of Circular Mound is on the south side, whereas the Imperial Vault of Heaven Complex is to the north. They were both the venues where the Ming and Qing emperors offered sacrifices to heaven, but they prayed for different things at different times and routes.

The altars’ construction and scenery design corresponded to the functional theme of offering sacrifices to the Supreme Deity of Heaven. The two main altars were both round, unlike the other square ones. Their three-layered structures taper on the top. The Altar of Circular Mound’s railing components are all yang in number (odd numbers), conforming to the theme of worshiping heaven. The Hall of Prayer for Good Harvest is covered with a round, pyramidal roof of blue-glazed tiles (unlike the yellow-, green-, and black-glazed tiles more frequently seen on other royal buildings) to symbolize the azure sky.

The emperor performed the ritual of offering sacrifices to heaven at the Altar of the Circular Mound every winter solstice to pray for the blessing of Hao Tian; the emperor also performed the ritual of praying at the Altar of Prayer for Grain in the first month of the lunar calendar every year, to pray for a good annual harvest.

The ceremony conducted by the emperors to offer sacrifices to the Supreme Deity of Heaven was highly elaborate, with overall similarities during the Ming and Qing dynasties, except for some minor differences in details. This article takes the Qing Dynasty ritual as an example for illustration. The emperor must go through an obligatory fast in the Forbidden City three days before the ceremony. He must ask his ancestors at the Imperial Ancestral Temple for permission before worshiping heaven in winter. The emperor must abstain from eating meat during the fast. Nor could he engage in entertainment or sleep with his concubines.

Collected Statutes of the Great Qing

The layout of the Temple of Heaven in the reign of

Emperor Jiaqing displayed in the Daqing Huidian

A day before the sacrifice-offering ceremony, the emperor would take the ceremonial sedan chair carried by 16 people and leave the imperial palace. In winter, he would change to another sedan chair, be carried southward along Beijing Central Axis to the Temple of Heaven, and enter it through the west gate. The sedan chair would stop at the Zhaohengmen Gate. Preparations for the ceremony would begin, and the emperor would offer incense and inspect the to-be-sacrificed animals and the altar before settling in the Hall of Fast in the Temple of Heaven to rest. When praying for a good harvest in mid-spring, the emperor would change to another sedan chair at the Tiananmen Gate and enter the Temple of Heaven through the Gate of Praying for Good Harvest.

On the winter solstice or mid-spring day, the emperor would take the sedan chair to the bridge on the south side of the altar and walk to it to participate in the sacrificial ceremony. After the ceremony, he would return to the palace along Beijing Central Axis in his sedan chair.

The Zhonghe Shaoyue (literally “Balanced music of Dashao”) was played during the ritual of offering sacrifices to heaven. It was a traditional ceremonial performance on main national occasions of royal rituals of offering sacrifices at imperial ancestor temples or altars of land and grain and grand banquets. The music has been listed as an important national intangible cultural heritage. West of the Outer Altar of the Temple of Heaven is the Divine Music Administration, specifically responsible for ritual music performance. It was also a school of rites training music and dance students. Today, it has become a venue to demonstrate the intangible cultural heritage of Zhonghe Shaoyue by way of performance.

The Hall of Prayer for Good Harvests

The Hall of Prayer for Good Harvests is on the Altar of Prayer to the God of Grains with a roof of blue-glazed tiles to symbolize the azure sky.

According to Liji - Jitong (A Summary of Sacrifices), “The Son of Heaven (emperors) plows the fields in person in the southern suburbs to grow crops for sacrifices.” The siting of the Altar of the God of Agriculture followed the tradition of plowing in the southern suburbs.

Three deities were worshiped in the Altar of the God of Agriculture during the Ming and Qing dynasties. In the inner part of the altar, the Altar of the God of Agriculture, the jitian (plot plowed by the emperor), and the Plowing Viewing Platform constituted an organic venue for the jitian-plowing ceremony. The plot, whose size, “one acre and three fen of land,” has since become part of the Chinese lexicon, was used for the emperor, the princes, the dukes, and the ministers to plow as a demonstration. The platform was where the emperor viewed the scene of the others plowing the fields. North of the inner part of the altar is the Hall of the God of the Year, a venue to worship the God of the Year and the twelve-month gods. The Altars of Heaven and Earth Gods are in the north of the inner part of the Altar of the God of Agriculture. It is a place to worship the celestial gods, like the Gods of Wind, Rain, and Thunder, and the terrestrial gods, like the Gods of Mountains, Rivers, and Seas.

Tilling the land in person and worshiping the Altar of the God of Agriculture, the emperor emphasized agricultural activities. It was especially important in the Qing dynasty because the Manchu ruling class used to be nomadic. Therefore, the emperors wanted to show their respect for the farming culture to appease the agrarian Chinese by worshiping the Altar of the God of Agriculture and plowing the fields in person. Their plowing ceremony was frequent for that purpose: The Ming emperors tilled or asked their proteges to work in their places 34 times. The Qing emperors performed as many as 247 times. Emperors Kangxi and Qianlong alone performed 58 times.

Location for the emperor to view ministers and dukes

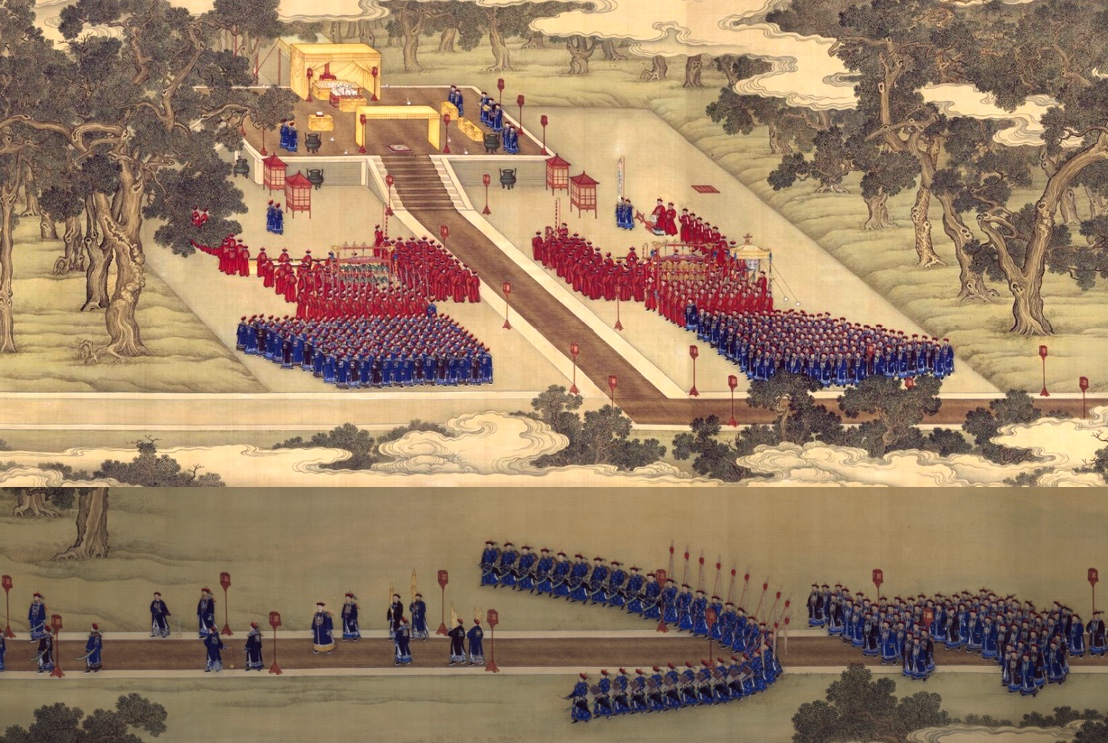

The most ceremonial activity of the unique rituals performed in the Altar of the God of Agriculture was the emperor’s demonstration of tilling the land, which normally happened in the 2nd lunar month of the year. The Qing dynasty’s scroll painting titled Yongzheng Emperor Offering Sacrifice at the Altar of the God of Agriculture clearly and vividly shows the entire process of Emperor Yongzheng performing the ritual. The image of him praying to the Altar of the God of Agriculture and holding the plow in the fields was particularly eye-catching.

Emperor Yongzheng offered sacrifices to the God of Agriculture at the Altar of the God of Agriculture first. The altar is square-shaped. A carpet was spread on it with a yellow canopy set up over it. Inside was an altar table laid out with sacrifices. Dressed in his best, Emperor Yongzheng walked by the Hall of Prayers and to the altar on the carpet. The dressed-up ministers and bodyguards were waiting before the altar already.

Yongzheng Emperor Offering Sacrifice at the Altar of the God of Agriculture

Source: The painting is currently housed at the Palace Museum.

Emperor Yongzheng walks toward the Altar of the God of Agriculture, where sacrifices have been laid out on the altar table.

The emperor would come to the jitian plot to plow it after finishing the sacrificial ceremony at the Altar of the God of Agriculture. The second part of The Yongzheng Emperor Offering Sacrifice at the Altar of the God of Agriculture shows Emperor Yongzheng tilling the plot, holding the plow in his right hand and a whip in his left, with the princes, dukes, and minsters watching. According to the Twenty-sixth Volume of the Collected Statutes of the Great Qing, the emperor would plow back and forth three times to the accompaniment of music. The vice minister would sow the seeds. After the ritual, the emperor would step up to the Plowing Viewing Platform to watch the dukes and other ministers repeat the ritual. The times of plowing were in keeping with the officials’ ranks. The emperor would assign special people to care for the fields, and the cereal crops would be harvested in autumn and stored in the Divine Granary. The product would be used to offer to the gods of heaven and earth.